NOTE: This is an updated post. If you were following discussion threads before 0200 hrs, 26 January, please refer to the original post here.

The original post was meant not as an journalistic article, but an interview vignette, featuring the ideas of one interviewee. This post is crafted in this style. I will make this clear in future similar posts. I have also explored the interviewee’s views more fully here.

———

The reasoning is common sense. The government of any country works towards economic growth. By developing their industries and housing their people, they degrade the natural environment. After achieving the prosperity they want, they can then look after the remaining green spaces.

Wealthy Singapore can — and is — is now doing just that, both at a government and citizen level, observes Professor Euston Quah, the head of Nanyang Technological University’s economics department.

But while environmentalists advocate preserving Singapore’s vestiges of woodlands and coasts, and developers talk about ‘developing sustainably’, he offers an uncommon reasoning for deciding how land-scare Singapore should apportion its land.

Every parcel of land has a price tag, he says, and how it is used should be decided by the highest bidder. Prof Quah’s maxim: “Nothing is free”.

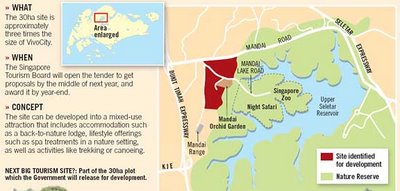

Take the 30-hectare parcel of land in Mandai that is set to be developed into a nature-themed attraction. On one side stand the developers, who will build Singapore Tourism Board’s project. STB hopes it will double the number of visitors to the Mandai area to five million and help treble tourism receipts in Singapore to $30 billion by 2015.

On the other side stands the value of the biodiversity — the woodland is home to the rare leopard cat, among other animals — and the value conservationists and the public place on it. But how does one value these intangibles?

Mandai roadmap: Expected to complement the adjacent Singapore Zoo and Night Safari, the planned nature-themed resort will both monetarise and degrade the existing plot of secondary forest. | Image: The Straits Times

It could go either way, but preserving it on the basis of petitions is not enough, he says. Chek Jawa was saved in 2001 by its popularity and biodiversity, but he calls the decision-making process too ad hoc for guiding future decisions.

Use the ‘cost and benefit analysis’ method, advocates Prof Quah.

To calculate the cost of losing the nature area, start with the ‘willingness-to-pay method’. For example, to find out how much are people willing to pay to keep the Mandai area, create a hypothetical admission fee to the land. Ask a representative sample of the stake-holding segment above what price they would not pay to enter. Multiply this by the number of stakeholders, and one can arrive at the monetary value of the appreciation of the area.

The ‘cost’ analysis also needs to include things such as the value of fresh air and clean water the area creates, he says.

Thirdly, include the value of the scenic views the area creates to get a full picture of the cost of losing the land to development. To estimate this, Prof Quah suggests observing real market prices of property commanding views of nearby green spaces.

The combined value of these indicators should then be weighed against the value of the ‘benefits’ of the development. This comes mainly from the expected profit of developing the land.

However, Prof Quah says the downsides of the development must be factored in as well. “On the other side, even building an MRT creates congestion and noise,” he says. “It ought to be imputed in, then we will get an idea of true cost to society.”

If the final cost falls below the developer’s estimate of its value, the land should be sold to the developer. If it is higher, the land should be preserved. “This has been done in the west, with a proper auction in a proper survey,” he says. “Singapore can and should do it too.”

But can we really price a stroll in the park after a hard day’s work? Are nature areas in land-scare Singapore not priceless?

His straightforward answer: No. Everything can — and must — be measured, says the professor, who is also an adviser to various ministries and statutory boards in Singapore.

“People must be educated. Keeping the land as it is has a price,” he says. “It doesn’t mean that if you enter for free, it is free. It can’t be. It is very costly.”

If money grows on trees: Green spaces occupy only a fraction of Singapore’s land, but for Prof Quah, their fate should be subjected to a monetary-based cost and benefit analysis. | Image: NParks

The professor says Singaporeans must understand that if the government leaves expanses green spaces alone, it would cause housing and industry congestion. This would cause rental prices and business costs to balloon. Investors would eventually leave.

“That’s worrying. The more you keep land as pristine as it is, the higher the opportunity cost will be,” he says. “There is no such thing as free.”

Because of Singapore’s premium on space, there is little room for error, says Prof Quah. Decision makers must then adhere to a disciplined method to allocate land. Error-minimisation is one of Singapore’s sacred cows, and he says this method ties in with the dollar-driven priorities of the government.

“It’s not the answer that’s important,” explains Prof Quah. “If you follow the process, the answers will be roughly correct. Without it, how will they decide?“You must understand, what drives Singapore is not the environment,” he says. “Singapore’s bread and butter is industry, growth. Singapore operates on this principle.”

If the value of the land preserves it under his cost-benefit analysis proposal, then all and good. Prof Quah realises that Singaporeans are treasuring their environment more and more.

“When we have too much industry, people’s voices will be heard. We want a balancing of the green and costs to society,” he says. What is Singapore’s next stage? Quality of life. That will include more green spaces, definitely.”

budak said,

January 25, 2008 @ 5:00 am

it seems to me that Prof Quah’s way of valuing nature is ad hoc as well, as it seems to rely on the population’s subjective assessment of the land’s value. One could argue that using purely monetary measurements on the worth of nature areas could well result in the economically ‘optimal’ outcome of nearly zero nature areas as people accord more value to ‘development’ in total, without taking into account the services (both measurable and less so) than nature areas provide.

chuaclarence said,

January 28, 2008 @ 7:18 am

To see Dr. Ho Hua Chews perspectives on this issue, please find:

“Environmental Values and the Willingness to Pay” in Environmental Issues in Development & Conservation (edited by Clive Briffett & Sim Loo Lee. SNP Publishers.)

Available in the NUS library.

chun fong said,

March 25, 2008 @ 4:03 am

i feel that it is not so simple as asking people for their opinion on how much a biodiversity-rich piece of land should cost, as people changes with time and what an earlier generation deems as dispensable may not be so for the next subsequent generation(s). hence i do not agree with the monetary assessment of land. indeed, nature is priceless.